[Editor’s Note: Leigh R. Hendry is the guest curator of Picasso Ceramics: Master in Clay Part II, which is on display at the Monthaven Arts and Cultural Center from Sept. 17 to Nov. 12,2023. Her essay below is taken from the exhibition’s program book.]

Often asked to guide collectors through the Herculean labyrinth of Picasso’s genius and his body of work, noted art historian Morris Shapiro, describes the request as “an impossible task.” Over the years, though, he said, he’s “come to realize that a helpful jumping-off point is to view Picasso’s identity as a complete artistic anthropological world: imagine a lost civilization newly discovered, where, at each level of the archaeological dig, another aspect of this mysterious, yet fully formed, evolving culture, is revealed.” Shapiro explains that at any point along Picasso’s path, viewers will “perceive another facet of the artist’s identity, which is like none other, and yet, remains instantly recognizable, as Picasso.” [1]

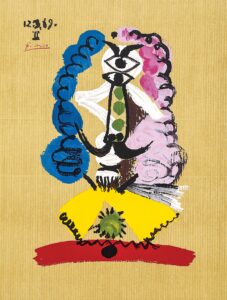

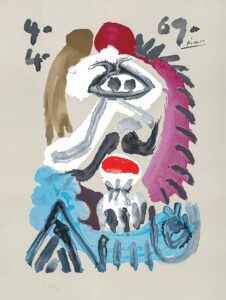

In 1969, when Picasso made the Imaginary Portraits, and actually for quite some time prior—between six and seven years—he was consistently being confronted with the iconoclastic contemporary movements of Pop Art [2] and Conceptualism, which had firmly seized the stage as the latest obsession of the art world’s arbiters.

In 1969, when Picasso made the Imaginary Portraits, and actually for quite some time prior—between six and seven years—he was consistently being confronted with the iconoclastic contemporary movements of Pop Art [2] and Conceptualism, which had firmly seized the stage as the latest obsession of the art world’s arbiters.

Undaunted, dedicated to aesthetic glory and as seemingly inexhaustible as ever, Picasso appeared unfazed by the task of challenging the artistic order of the day, with its focus on definitions of what was (and what wasn’t) “art.” With that as his impetus, the mercurial Spaniard threw himself headlong into the frenzied creation of 29 large format gouache and oil paintings.

Always inventive, Picasso created the pictures using sheets of brown corrugated cardboard, which had been salvaged from oversized packages delivered to his studio in Mougins, France. Rather than viewing the cardboard as refuse, Picasso classified it instead as “blank canvas.” Innovator that he was, Picasso had a long-term abiding interest in the utilization of unique surfaces for making art, not to mention having constructed a plethora of outstanding collages in his career, he was no stranger to the inclusion of unexpected materials.

The result of the work that Picasso made during this late-life-obsessive-burst-of-creativity was the marvelous series known as the Imaginary Portraits. The dozen works from the suite on view in this exhibition provide visitors with a sampling generous enough to encourage art enthusiasts to seek out the remaining 17 images.

Realized through color lithography by the incomparable printer, Marcel Salinas (1913-2010), an Egyptian of Italian/French descent, the series was published in portfolio through Éditions Cercle d’Art, in Paris, and Harry Abrams, Inc. in New York. The complete edition consisted of 500 examples, annotated “F” and “A” (F for the works to be distributed in France and A for distribution to the American art market and the rest of the world) and numbered. Salinas, as much of a purist as Picasso [3] and an artist himself, spent 12 intense months perfecting the printing plates. They were of such exceptional quality that Picasso reportedly insisted that Salinas’ unparalleled work receive equal recognition to his. Salinas was also selected by Picasso’s family to oversee the production of other lithographs made after the artist had passed away.[4]

Realized through color lithography by the incomparable printer, Marcel Salinas (1913-2010), an Egyptian of Italian/French descent, the series was published in portfolio through Éditions Cercle d’Art, in Paris, and Harry Abrams, Inc. in New York. The complete edition consisted of 500 examples, annotated “F” and “A” (F for the works to be distributed in France and A for distribution to the American art market and the rest of the world) and numbered. Salinas, as much of a purist as Picasso [3] and an artist himself, spent 12 intense months perfecting the printing plates. They were of such exceptional quality that Picasso reportedly insisted that Salinas’ unparalleled work receive equal recognition to his. Salinas was also selected by Picasso’s family to oversee the production of other lithographs made after the artist had passed away.[4]

This series stands as a delightful visual romp with a cast of colorful “imaginary” characters. As has been documented, Picasso rarely made a work of art without including an allusion to art history. Accordingly, he features a pair of his artistic heroes in the Imaginary Portraits. There’s Rembrandt (Dutch,1606-1669), the father of “psychological portraiture,” [5] of course, who takes center stage and is identifiable by the 17th century costume fragments adorning many of the characters, as well as the shining star of the Spanish Golden Age, Diego Velázquez (c.1599-1660). The citing of virtuoso Velázquez as one of Picasso’s most revered heroes, recalls a previous “metaphorical” encounter between the two painters: more than a decade earlier, Picasso created 58 paintings [6] based upon the Velázquez masterpiece, Las Meninas (The Ladies-in-Waiting),1656.

Not to be overlooked, particularly considering Picasso’s fascination with the female form, there are feminine figures in the Imaginary Portraits, too, both as a nude artist’s model, and as a sophisticate, resplendent in a Spanish mantilla. The flamboyant trio of Balzac (French, novelist/playwright, 1799-1850), Goya (Spanish, painter,1746-1828), and Shakespeare (English, playwright/actor/poet, 1564-1616) also make swashbuckling appearances.

“Ultimately,” Shapiro says the Imaginary Portraits suite, “as amongst the final creations of Picasso’s life, deftly underscores the incomparable vigor, the unbridled creativity and the complete fearlessness still possessed by this man in his late 80s—-the conquerer of the 20th century art world, the undisputed leader of the avant-garde of his time, and one of the greatest artistic giants to ever draw breath in the history of the human experience.”

1. Morris Shapiro, email message to Leigh R. Hendry, August 8, 2023

2. Tony Scherman, “When Pop Turned The Art World Upside Down,” accessed August 5, 2023, https://www.americanheritage.com/when-pop-turned-art-world-upside-down

3. Tess McRae, “Meet the man behind Picasso’s prints: Marcel Salinas,” accessed August 12, 2023, https://www.qchron.com/qboro/stories/meet-the-man-behind-picasso-s-prints-marcel-salinas/article_cbc34890-15c4-5171-b87f-067d56e2b51a.html

4. Bruce Rushton,”The Master,” accessed August 11, 2023, https://www.riverfronttimes.com/.news/themaster-2468068

Cheryl Van Buskirk, “Rembrandt van Rijn Artist Overview and Anaysis,” accessed August 17, 2023,

5. Iliana Gutierrez, “Pablo Picasso: The Many Iterations of Las Meninas—Noble Oceans,” accessed August 22, 2023, https://www.nobleoceans.com/artists/2017/4/4/pablo-picasso-the-many-iterations-of-las-meninas